CI/CD development guidelines

CI/CD pipelines are a fundamental part of GitLab development and deployment processes, automating tasks like building, testing, and deploying code changes. When developing features that interact with or trigger pipelines, it’s essential to consider the broader implications these actions have on the system’s security and operational integrity.

This document provides guidelines to help you develop features that use CI/CD pipelines securely and effectively. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the implications of running pipelines, managing authentication tokens responsibly, and integrating security considerations from the beginning of the development process.

General guidelines

- Recognize pipelines as write operations: Triggering a pipeline is a write operation that changes the system’s state. The write operation can initiate deployments, run tests, or alter configurations. Treat pipeline triggers with the same caution as other critical write operations to prevent unauthorized changes or misuse of the system.

- Running a pipeline should be an explicit action: Actions that create a pipeline in the user’s context should be designed so that it is clear to the user that a pipeline (or single job) is started when performing the action. The user should be aware of the changes executed in the pipeline before they are executed.

- Remote execution and isolation: The CI/CD pipeline functions as a remote execution environment where jobs can execute scripts performing a wide range of actions. Ensure that jobs are adequately isolated and do not unintentionally expose sensitive data or systems.

- Collaborate with AppSec and Verify teams: Include Application Security (AppSec) and Verify team members early in the design process and when drafting proposals. Their expertise can help identify potential security risks and ensure that security considerations are integrated into the feature from the outset. Additionally, involve them in the code review process to benefit from their specialized knowledge in identifying vulnerabilities and ensuring compliance with security standards.

- Determine the pipeline actor: When building features that trigger pipelines, it’s crucial to consider which user initiates the pipeline. You need to determine who should be the actor of the event. Is it an intentional pipeline run where a user directly triggers the pipeline (for example by pushing changes to the repository or clicking the “Run pipeline” button), or is it a pipeline run initiated by the GitLab system or a policy? Avoid scenarios in which the user creating the pipeline is not the author of the changes. If the users are not the same, there is a risk that the author of the changes can run code in the context of the pipeline user. Understanding the actor helps in managing permissions and ensuring that the pipeline runs in the correct execution context.

- Variability of job execution users: The user running a specific job might not be the same user who created the pipeline.

While in the majority of cases the user is the same, there are scenarios where the user of the job changes, for example when

running a manual job or retrying a job. This variability can affect permissions and access levels in the job’s execution

context. Always account for this possibility when developing features that use the CI/CD job token (

CI_JOB_TOKEN). Consider whether the job user should change and who the actor of the action is. - Restrict scope of the operation: When enabling a new endpoint for use with the CI/CD job token, strongly consider limiting operations to the same job, pipeline, or project to enhance security. Strongly prefer the smaller scope (job) over larger scope (project). For example, if allowing access to pipeline data, restrict it to the current pipeline to prevent cross-project or cross-pipeline data exposure. Evaluate whether cross-project or cross-pipeline access is truly necessary for the feature; limiting the scope reduces security risks.

- Monitor and audit activities: Ensure that the feature is auditable and monitorable. Introduce detailed logs of events that would trigger a pipeline, including the pipeline user, the actor initiating the action, and event details.

Other guides

Development guides that are specific to CI/CD are listed here:

- If you are creating new CI/CD templates, read the development guide for GitLab CI/CD templates.

- If you are adding a new keyword or changing the CI schema, refer to the following guides:

- If you are making a change to core CI/CD process such as linting or pipeline creation, refer to the CI/CD testing guide

See the CI/CD YAML reference documentation guide to learn how to update the CI/CD YAML syntax reference page.

Metrics

This section describes the dashboards and metrics that can be used by engineers during development, change validation and incident investigation.

- Dashboards for all GitLab teams are available. You can search for the team that owns the feature category you are interested in.

- The Pipeline Execution error budget dashboard contains other useful metrics about pipeline creation and job execution.

- Production logs also offer many useful information that can be searched and aggregated in Kibana.

- The Pipeline creation dashboard provides useful breakdowns of the steps involved in the pipeline creation. Note that this dashboard only contains data of “slow pipelines”, those that take longer to be created or have many jobs in it. It’s similar to a SQL “slow query log”.

- The CI partitioning dashboard contains information about the current partition number, partition sizes, vacuuming, and other database metrics.

Examples of CI/CD usage

We maintain a ci-sample-projects group, with projects that showcase

examples of .gitlab-ci.yml for different use cases of GitLab CI/CD. They also cover specific syntax that could

be used for different scenarios.

CI Architecture overview

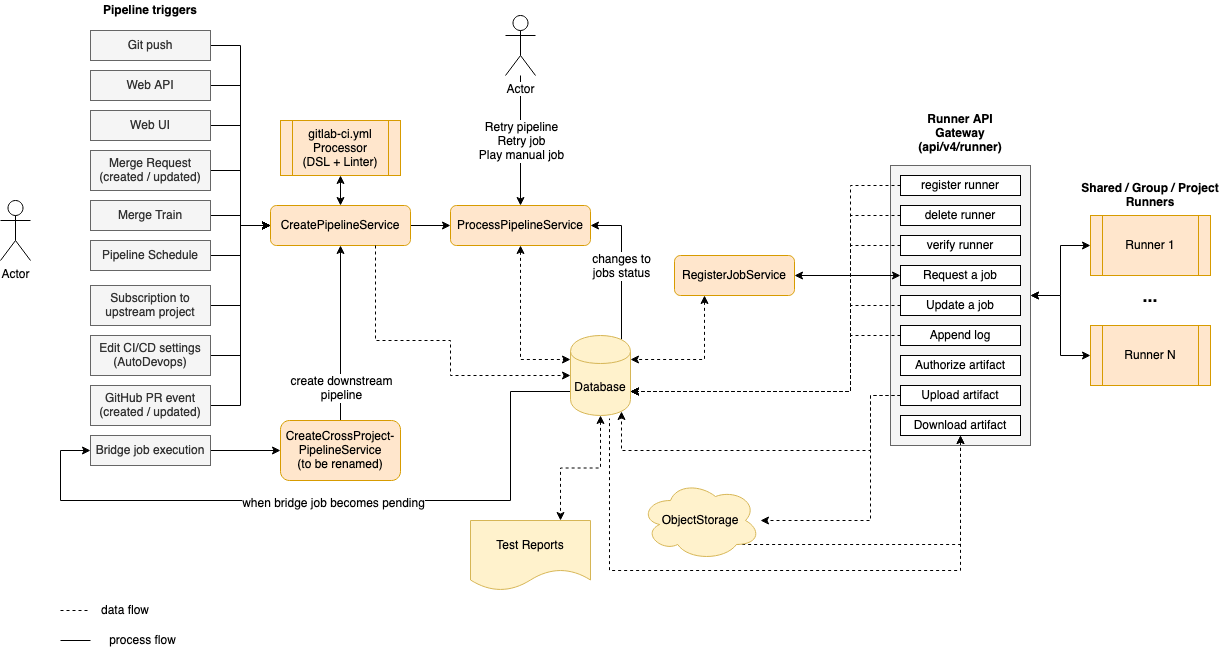

The following is a simplified diagram of the CI architecture. Some details are left out to focus on the main components.

On the left side we have the events that can trigger a pipeline based on various events (triggered by a user or automation):

- A

git pushis the most common event that triggers a pipeline. - The Web API.

- A user selecting the “Run pipeline” button in the UI.

- When a merge request is created or updated.

- When an MR is added to a Merge Train.

- A scheduled pipeline.

- When project is subscribed to an upstream project.

- When Auto DevOps is enabled.

- When GitHub integration is used with external pull requests.

- When an upstream pipeline contains a bridge job which triggers a downstream pipeline.

Triggering any of these events invokes the CreatePipelineService

which takes as input event data and the user triggering it, then attempts to create a pipeline.

The CreatePipelineService relies heavily on the YAML Processor

component, which is responsible for taking in a YAML blob as input and returns the abstract data structure of a

pipeline (including stages and all jobs). This component also validates the structure of the YAML while

processing it, and returns any syntax or semantic errors. The YAML Processor component is where we define

all the keywords available to structure a pipeline.

The CreatePipelineService receives the abstract data structure returned by the YAML Processor,

which then converts it to persisted models (like pipeline, stages, and jobs). After that, the pipeline is ready

to be processed. Processing a pipeline means running the jobs in order of execution (stage or needs)

until either one of the following:

- All expected jobs have been executed.

- Failures interrupt the pipeline execution.

The component that processes a pipeline is ProcessPipelineService which handles:

- Setting jobs to their initial states of

pendingif they’re ready to run orcreatedif they’re waiting on dependent jobs - Updating jobs to

pendingbased on recently completed dependent jobs - Updating pipelines and stages to match the overall status of the collection of jobs

On the right side of the diagram we have a list of runners

connected to the GitLab instance. These can be instance runners, group runners, or project runners.

The communication between runners and the Rails server occurs through a set of API endpoints, grouped as

the Runner API Gateway.

We can register, delete, and verify runners, which also causes read/write queries to the database. After a runner is connected,

it keeps asking for the next job to execute. This invokes the RegisterJobService

which picks the next job and assigns it to the runner. At this point the job transitions to a

running state, which again triggers ProcessPipelineService due to the status change.

For more details read Job scheduling).

While a job is being executed, the runner sends logs back to the server as well any possible artifacts that must be stored. Also, a job may depend on artifacts from previous jobs to run. In this case the runner downloads them using a dedicated API endpoint.

Artifacts are stored in object storage, while metadata is kept in the database. An important example of artifacts are reports (like JUnit, SAST, and DAST) which are parsed and rendered in the merge request.

Job status transitions are not all automated. A user may run manual jobs, cancel a pipeline, retry

specific failed jobs or the entire pipeline. Anything that

causes a job to change status triggers ProcessPipelineService, as it’s responsible for

tracking the status of the entire pipeline.

A special type of job is the bridge job which is executed server-side

when transitioning to the pending state. This job is responsible for creating a downstream pipeline, such as

a multi-project or child pipeline. The workflow loop starts again

from the CreatePipelineService every time a downstream pipeline is triggered.

You can watch a walkthrough of the architecture in CI Backend Architectural Walkthrough.

Pipeline processing

When a pipeline is created, the ProcessPipelineService runs automatically via Ci::InitialPipelineProcessWorker.

This service is also triggered via PipelineProcessWorker whenever a job changes statuses.

This service is responsible for moving all the pipeline’s jobs to a completed state by setting them to either:

pendingstatus if their requirements are met and they’re ready to run and can be picked up by a runnercreatedstatus if they need to wait, withprocessedmarked astrue

After a job has been executed it can complete successfully or fail. Each status transition for a job within a pipeline triggers this service again, which looks for the next jobs to be transitioned towards completion. While doing that, ProcessPipelineService updates the status of jobs, stages and the overall pipeline. If any jobs require further processing, the service will reschedule itself.

The processed flag acts as a “needs processing” indicator that gets reset to false before each status transition. This ensures that whenever a job’s status changes, those changes are propagated to the stage and pipeline levels, and later builds and next builds in the DAG can be marked as pending. The job won’t be marked as processed until the state is also propagated to the pipeline and stage.

Retry behavior and self-healing

The PipelineProcessWorker uses an exponential backoff that provides self-healing capabilities for pipelines when encountering intermittent errors.

If processing fails due to temporary issues (such as database timeouts, Redis errors, or out-of-memory conditions), the worker retries with increasing delays.

Since the worker is idempotent and checks that jobs and pipelines need_processing?, it can safely execute multiple

times. This retry mechanism can fix pipelines where all jobs are completed but the pipeline was not marked as completed

due to a temporary error during processing.

Job scheduling

When a Pipeline is created all its jobs are created at once for all stages, with an initial state of created. This makes it possible to visualize the full content of a pipeline.

A job with the created state isn’t seen by the runner yet. To make it possible to assign a job to a runner, the job must transition first into the pending state, which can happen if:

- The job is created in the very first stage of the pipeline.

- The job required a manual start and it has been triggered.

- All jobs from the previous stage have completed successfully. In this case we transition all jobs from the next stage to

pending. - The job specifies needs dependencies using

needs:and all the dependent jobs are completed. - The job has not been dropped because of its not-runnable state by

Ci::PipelineCreation::DropNotRunnableBuildsService.

When the runner is connected, it requests the next pending job to run by polling the server continuously.

API endpoints used by the runner to interact with GitLab are defined in lib/api/ci/runner.rb

After the server receives the request it selects a pending job based on the Ci::RegisterJobService algorithm, then assigns and sends the job to the runner.

Once all jobs are completed for the current stage, the server “unlocks” all the jobs from the next stage by changing their state to pending. These can now be picked by the scheduling algorithm when the runner requests new jobs, and continues like this until all stages are completed.

Communication between runner and GitLab server

After the runner is registered using the registration token, the server knows what type of jobs it can execute. This depends on:

- The type of runner it is registered as:

- an instance runner

- a group runner

- a project runner

- Any associated tags.

The runner initiates the communication by requesting jobs to execute with POST /api/v4/jobs/request. Although polling happens every few seconds, we leverage caching through HTTP headers to reduce the server-side work load if the job queue doesn’t change.

This API endpoint runs Ci::RegisterJobService, which:

- Picks the next job to run from the pool of

pendingjobs - Assigns it to the runner

- Presents it to the runner via the API response

Ci::RegisterJobService

This service uses 3 top level queries to gather the majority of the jobs and they are selected based on the level where the runner is registered to:

- Select jobs for instance runner (instance-wide)

- Uses a fair scheduling algorithm which prioritizes projects with fewer running builds

- Select jobs for group runner

- Select jobs for project runner

This list of jobs is then filtered further by matching tags between job and runner tags.

If a job contains tags, the runner doesn’t pick the job if it does not match all the tags. The runner may have more tags than defined for the job, but not vice-versa.

Finally if the runner can only pick jobs that are tagged, all untagged jobs are filtered out.

At this point we loop through remaining pending jobs and we try to assign the first job that the runner “can pick” based on additional policies. For example, runners marked as protected can only pick jobs that run against protected branches (such as production deployments).

As we increase the number of runners in the pool we also increase the chances of conflicts which would arise if assigning the same job to different runners. To prevent that we gracefully rescue conflict errors and assign the next job in the list.

Dropping stuck builds

There are two ways of marking builds as “stuck” and drop them.

- When a build is created,

Ci::PipelineCreation::DropNotRunnableBuildsServicechecks for upfront known conditions that would make jobs not executable:- If there is not enough CI/CD Minutes to run the build, then the build is immediately dropped with

ci_quota_exceeded. - In the future, if the project is not on the plan that available runners for the build require via

allowed_plans, then the build is immediately dropped withno_matching_runner.

- If there is not enough CI/CD Minutes to run the build, then the build is immediately dropped with

- If there is no available Runner to pick up a build, it is dropped after 1 hour by

Ci::StuckBuilds::DropPendingService.- If a job is not picked up by a runner in 24 hours it is automatically removed from the processing queue after that time.

- If a pending job is stuck, when there is no runner available that can process it, it is removed from the queue after 1 hour.

- In both cases the job’s status is changed to

failedwith an appropriate failure reason.

The reason behind this difference

Compute minutes quota mechanism is handled early when the job is created because it is a constant decision for most of the time. Once a project exceeds the limit, every next job matching it will be applicable for it until next month starts. Of course, the project owner can buy additional minutes, but that is a manual action that the project need to take.

The same mechanism will be used for allowed_plans soon.

If the project is not on the required plan and a job is targeting such runner,

it will be failing constantly until the project owner changes the configuration or upgrades the namespace to the required plan.

These two mechanisms are also very SaaS specific and at the same time are quite compute expensive when we consider SaaS’ scale. Doing the check before the job is even transitioned to pending and failing early makes a lot of sense here.

Why we don’t handle other cases for pending and drop jobs early? In some cases, a job is in pending only because the runner is slow on taking up jobs. This is not something that you can know at GitLab level. Depending on the runner’s configuration and capacity and the size of the queue in GitLab, a job may be taken immediately, or may need to wait.

There may be also other reasons:

- you are handling runner maintenance and it’s not available for a while at all,

- you are updating configuration and by mistake, you’ve messed up the tagging and/or protected flag (or in the case of our SaaS instance runners; you’ve assigned a wrong cost factor or

allowed_plansconfiguration).

All of that are problems that may be temporary and mostly are not expected to happen and are expected to be detected and fixed early. We definitely don’t want to drop jobs immediately when one of these conditions is happening. Dropping a job only because a runner is at capacity or because there is a temporary unavailability/configuration mistake would be very harmful to users.

Job Trace Chunk Architecture

On GitLab.com, when traces are sent from a runner the content is stored in a redis_trace_chunks Redis cluster with a key containing the job ID and index.

A Ci::BuildTraceChunk record is also created to keep track of each chunk. This record indicates the current data store for the chunk. Admins of a GitLab

installation can configure which data stores are used. On non-GitLab.com instances, this behavior also occurs when ci_job_live_trace_enabled? is enabled.

Lifecycle

- Trace Append Phase

- Runner →

PATCH /api/v4/jobs/1/trace(sends trace contents) Ci::AppendBuildTraceServicestores chunk data in the live store (Redis trace chunks cluster for .com)- Creates

Ci::BuildTraceChunkrecord in PostgreSQL withdata_store: redis_trace_chunks - Creates

Ci::BuildTraceMetadatarecord to track trace metadata - Returns 200 OK to Runner

build.trace_chunkswill contain records withredis_trace_chunksor another live store as thedata_store

- Runner →

- Job Update Phase

- Runner →

PUT /api/v4/jobs/1(job update) - This endpoint also runs

Ci::BuildTraceChunkFlushWorker Ci::BuildTraceChunkFlushWorkerretrieves chunk data from Redis trace chunks cluster- Copies chunk to object storage (each chunk gets its own file)

- Deletes live chunk from live data store (

redis_trace_chunkscluster on .com) - Updates

Ci::BuildTraceChunkrecord in PostgreSQL withdata_store: fog - Returns 200 OK to runner

build.trace_chunkswill contain records withfogor another persisted store as thedata_store

- Runner →

- Job Completion & Archive Phase

- Runner →

PUT /api/v4/jobs/1(job completion) - Triggers

Ci::BuildFinishedWorker Ci::ArchiveTraceWorkerretrieves all fog chunks from object storage- Creates single consolidated archive file as a

JobArtifactoftype: :trace - Deletes individual chunks from object storage

- Deletes

Ci::BuildTraceChunkrecords from PostgreSQLCi::Build::Tracechanges from thelivetoarchivedstate

- Returns 200 OK to runner

build.trace_chunkswill be an empty array

- Runner →

sequenceDiagram

participant Runner

participant API

participant Redis as Redis Trace Chunks

participant ObjectStorage as Object Storage

participant PostgreSQL

participant Archive as Archive Storage

Note over Runner, Archive: 1. Trace Append Phase

Runner->>API: PATCH /api/v4/jobs/1/trace<br/>(trace contents)

API->>Redis: Ci::AppendBuildTraceService<br/>stores chunk data

API->>PostgreSQL: Create Ci::BuildTraceChunk<br/>(data_store: redis_trace_chunks)

API->>Runner: 200 OK

Note over Runner, Archive: 2. Job Update Phase

Runner->>API: PUT /api/v4/jobs/1<br/>(job update)

API->>Redis: Ci::BuildTraceChunkFlushWorker<br/>retrieves chunk data

API->>ObjectStorage: Copy chunk to storage<br/>(each chunk = own file)

API->>Redis: Delete chunk in redis

API->>PostgreSQL: Update Ci::BuildTraceChunk<br/>(data_store: fog)

API->>Runner: 200 OK

Note over Runner, Archive: 3. Job Completion & Archive Phase

Runner->>API: PUT /api/v4/jobs/1<br/>(job completion)

API->>API: Trigger Ci::BuildFinishedWorker

API->>ObjectStorage: Ci::ArchiveTraceWorker<br/>retrieves all fog chunks

API->>Archive: Create single archive file

API->>ObjectStorage: Delete individual chunks

API->>PostgreSQL: Update Ci::Build::Trace<br/>(live → archived)

API->>Runner: 200 OK

Monitoring Resources

- Dashboard: Redis TraceChunks Overview

- Runbook: Redis TraceChunks Operations

The definition of “Job” in GitLab CI/CD

“Job” in GitLab CI context refers a task to drive Continuous Integration, Delivery and Deployment. Typically, a pipeline contains multiple stages, and a stage contains multiple jobs.

In Active Record modeling, Job is defined as CommitStatus class.

On top of that, we have the following types of jobs:

Ci::Build… The job to be executed by runners.Ci::Bridge… The job to trigger a downstream pipeline.GenericCommitStatus… The job to be executed in an external CI/CD system, for example Jenkins.

When you use the “Job” terminology in codebase, readers would

assume that the class/object is any type of above.

If you specifically refer Ci::Build class, you should not name the object/class

as “job” as this could cause some confusions. In documentation,

we should use “Job” in general, instead of “Build”.

We have a few inconsistencies in our codebase that should be refactored.

For example, CommitStatus should be Ci::Job and Ci::JobArtifact should be Ci::BuildArtifact.

See this issue for the full refactoring plan.